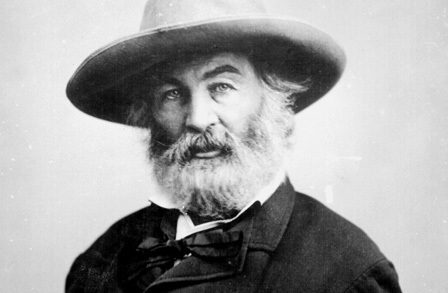

POETRY READING CLUB- POEM OF THE MONTH ANALYSIS: “O Me! O Life!” by Walt Whitman

This month, the star of our Poetry Reading Club is America’s first “celebrity poet”: Walt Whitman. Born in 1819, on Long Island, New York, Whitman lived through the great events of nineteenth-century America, i.e., the Civil War, the end of slavery, and the assassination of President Lincoln; westward expansion and the settling of the American prairie; industrialization, immigration and the growth of the city; much of his poetry engages in a dialogue with this rapidly-changing world. Indeed, the very notion of dialogue is essential to Whitman’s poetic sensibility. In “O Me! O Life!,” for example, the speaker seems at first to be engaged in dialogue with himself, questioning the world around him and his relation to it all. At the end of the poem, he receives his answer, but whether this is issued from the depths of his own consciousness or from a voice separate but close by is unclear. The origin of that voice is less important than the effect it has on us, its readers, which is to draw us more intimately into the dialogue of the poem: Whitman’s questions become our questions, his answers resonate with ours, his lamentations and joys are experienced as if they were our own.

Whitman’s poetry received mixed critical acclaim during his lifetime, although he was known across the Atlantic, where English writers such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Alfred, Lord Tennyson had read his work. Whitman corresponded with a number of these major poetic players of the era, as well as with American transcendentalists Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, receiving letters of praise, visits, and, on occasion, marriage proposals. Whitman’s legacy has endured and even flourished over time, in part because he was championed by later American poets William Carlos Williams and Allen Ginsberg, who found in Whitman a uniquely American poetic voice. These poets saw in Whitman a celebration of America, which is curious when we consider that the country was still relatively young during Whitman’s time. It was still divided by the conflicting ideologies that had caused the Civil War, and throughout the second half of the century the United States became home to an increasing number of European immigrants. The English, and English-speaking Scottish and Irish of the early colonial years were forced to make room for the Norwegian, Swedish, Germans, Italians, Polish, Eastern European Jews, Russians, and Greeks, who came flooding into the country hoping for a better life. What, then, was the America that Whitman so often celebrated in his poems? Who were its people, and what was their language?

Perhaps it is because the specifics of nationality, or rather, of ethnicity, are so often absent from Whitman’s poems, that what emerges instead is a sense of the uniqueness of the American spirit, as in the poem, “I Hear American Singing.” This is a spirit that is embodied equally by the people of the country as it is by the land itself: humble, hardworking, and honest. Whitman’s rejection of traditional poetical form and meter and his embracing of the rhythm and structure of Biblical poetry would later be appreciated by Williams and Ginsberg, as they, too, struggled to define and redefine the cultural and linguistic landscape of their country. The Whitman-esque desire for dialogue is evident in Ginsberg’s poem, “A Supermarket in California” (1955), where Ginsberg speaks directly to Whitman. The poem is an articulation of the desire for companionship, for camaraderie, as Ginsberg wanders through an American landscape that Whitman would perhaps not recognize.

If the journey from Whitman’s to Ginsberg’s America is a difficult one to plot, it is, surely, one which is accompanied by music. Whitman’s poems are, in my opinion, meant to be read out loud. The exclamation marks in the very title of “O Me! O Life!” require us to lift our voices just as we would if we were singing or exclaiming. Although there aren’t many recordings of Whitman reading his poetry, this doesn’t mean that we can’t experience the poems aurally. Try reading the lines below out loud, at home. Whenever there is a word in bold, emphasize that word, really exaggerate the emphasis, shout it, if you must.

Beat! beat! drums!—blow! bugles! blow!

Through the windows—through doors—burst like a ruthless force,

Into the solemn church, and scatter the congregation,

Into the school where the scholar is studying,

Leave not the bridegroom quiet—no happiness must he have now with his bride,

Nor the peaceful farmer any peace, ploughing his field or gathering his grain,

So fierce you whirr and pound you drums—so shrill you bugles blow.

What kinds of cadences, rhythms do you hear? Do you experience any emotions reading the poem out loud this way? How do you feel?

All the words in bold are verbs, and they are good, strong action verbs. We’ll talk about the strong dynamism of Whitman’s poetry, it’s particular American uniqueness, and its lasting effect on the American poetic canon on Tuesday. I look forward to hearing your thoughts…and to hearing your recitals of Whitman!

Happy Reading,

Chiara