POETRY READING CLUB- POEM OF THE MONTH ANALYSIS: “AMERICA” BY ALLEN GINSBERG

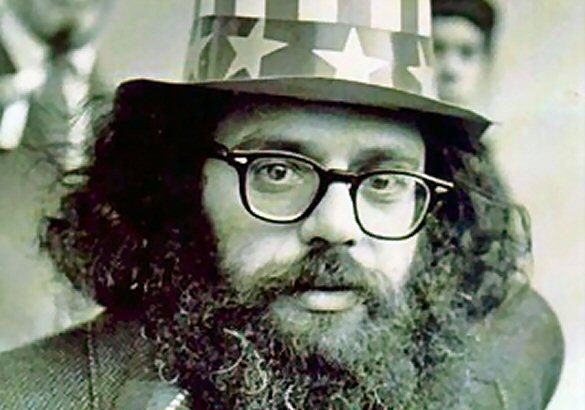

Visionary. Dreamer. Wanderer. Poet. The question is, who are we talking about, Walt Whitman or Allen Ginsberg? If we allow ourselves a little bit of poetic license to imagine a meeting between these two men, it’s not hard to picture the disciple sitting down at the feet of the spiritual teacher, or the younger brother seeking out the older one for advice; the influence of Whitman on Ginsberg’s poetry is unmistakable. But what was it, exactly, that Ginsberg was seeking when he turned to Whitman? A literary predecessor who was distinctly American? A fellow comrade or traveling companion? A hero, an idol? He could hardly have been looking for inspiration, for just like Whitman, Ginsberg used poetry as a way to engage with the world around him, and it was this living, breathing, real world that inspired his poems. And yet, the real world troubled Ginsberg as much as it inspired him. It is this sense of trouble, this inability to simply celebrate the world as Whitman did, that most distinguishes Ginsberg from Whitman, in spite of the noticeable similarities between the two.

It is also this sense of being troubled, I think, that prompts Ginsberg to evoke Whitman so directly in “A Supermarket in California” (1955). What had happened to America in the hundred years between the publication of Whitman’s Leaves of Grass (1855) and Ginsberg’s Howl and Other Poems (1956)? America in the 1950s had become a landscape of neon lights and blue automobiles parked outside every house. A Cold War paranoia emanated even from the supermarket store detectives. We can imagine Whitman being overwhelmed and perhaps a little dismayed by this vision of his beloved country. It’s no wonder that Ginsberg wants company, that he calls out to his “lonely old courage-teacher,” and longs to return “home to [their] silent cottage.” What do you think the “silent cottage” represents for Ginsberg? (Those of you who have read Howl will notice that the cottage also appears at the end of this poem as a place of refuge or rest.) A lost America? A place still inhabited by the American spirit of Whitman’s time?

In our last session, we described Whitman as a confident, young, self-promoter, a man who had just arrived, and who was eager to make his way in a country that had, in its own way, also just arrived. After the Second World War, American had, in a sense, “just arrived” a second time. The nation emerged triumphant from the war without any of the visible scars that would mark Europe for the next two decades. The economy was booming and life was good, at least on the surface of things. The price of this prosperity was a rigid conformity to the values of an increasingly consumerist society. The voice speaking to us from Ginsberg’s poems is a voice of protest against this society. It is also, at the same time, the voice of a lover pleading with his beloved, for there are often startling moments of earnestness when Ginsberg alternately embraces and then rejects the affinity with his country. Consider these lines from “America” (1956):

American I’ve given you all and now I’m nothing.

…

America after all it is you and I who are perfect not

the next world.

Your machinery is too much for me.

You made me want to be a saint.

These alternations of lamentation and hope are only partly inherited from Whitman. For even when Whitman laments the world around him, one that has perhaps modernized too quickly for his liking, with its “endless trains of the faithless” and its “plodding and sordid crowds,” he offers a final note of hope that redeems the world around him. That hopefulness, that pulse of life that Whitman transmits through his poems, is what makes them so uniquely his own, and so uniquely American. That hopefulness is there in Ginsberg’s poetry too, although it’s often mixed up with rage or despair. That rage, that despair, make these poems uniquely Ginsberg’s. And it is this rage and despair that also make possible a new, but equally unique, sense of hope that belongs to American life in the postwar era. Certainly, Ginsberg’s poems pulse with a life force of their own, one that belongs to the second half of the twentieth century, a world haunted by the fear of another atomic bomb. It often seems as if Ginsberg had his own dream for America, and that is a hopeful thing, even if that dream sometimes takes the form of a nightmare. When we think about the impact of both Whitman and Ginsberg, it is neither the dream nor the nightmare that makes their work so vital, but rather those waking moments when the poet is out in the world, chanting his words so that others may hear them.

Happy Reading, and Happy Listening (there is a recording of “A Supermarket in California” on poetryfoundation.com, accessible through the link above). Have a great weekend, and see you on Tuesday.

Chiara