- Posted: 20 abril, 2017

- By: Biblioteca

- Comments: No Comments

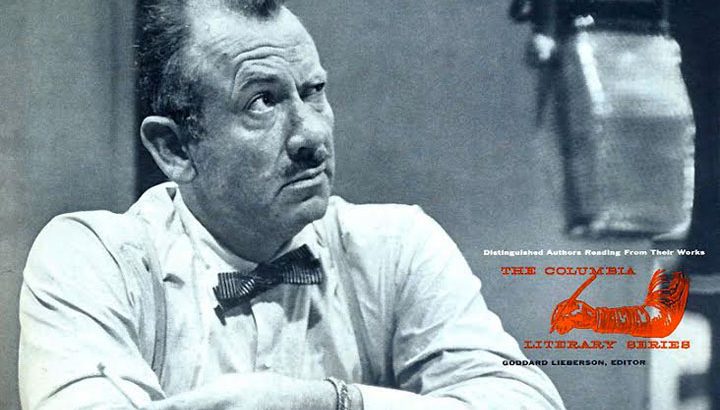

ENGLISH READING CIRCLE – SHORT STORY OF THE MONTH ANALYSIS: “THE SNAKE” BY JOHN STEINBECK

This month’s story is John Steinbeck’s “The Snake”, written in 1934 and published the year after. It forms part of The Long Valley collection, which was published in 1938. The story is set in Monterrey, California, and features a character, Dr. Phillips, that is based on the marine biologist and philosopher Ed Ricketts, a friend of Steinbeck’s who formed the basis for a number of different characters across his works. After the publication of the novel Cannery Row in 1945, in which a character based on Ricketts (Doc) figures prominently, he became something of a celebrity in Monterrey. Ricketts’ career blurred the conventional understanding of what a scientist is supposed to be. Steinbeck’s story, which relates a true-to-life episode that took place in Rickett’s seaside laboratory, presents the reader with a disconcerting scenario that calls into question some of science’s most fundamental justifications and guiding principles. Here we see that “science” is in the eye of the beholder, and so too is cruelty, and dark entertainment.

According to Steinbeck’s journal entries, this story was one that demanded to be written. Something about the incident haunted him; he could not say what the story meant, only that it seemed important to him, and worth preserving. Perhaps, in an ironic way, Steinbeck’s determination to document this eerie and singular interaction represents his own need to catalogue and analyze the mysteries of human experience, much like a scientist seeks to understand the mysteries of the natural world.

And much of this story is a mystery. Why must the woman own the snake? Why must the snake be male? Why, upon witnessing the snake feed, does the woman never return? What does Dr. Phillips find so disturbing about the woman’s fascination? We can hazard answers to these questions, and perhaps propose tenable interpretations (obviously there is a great deal of psychological symbolism at play here, a wealth of subconscious imagery), but the incident remains shrouded in doubt. There can be no clearly reasoned and well-evidenced conclusions to draw, as there should be with any credible scientific inquiry. We are simply left with a series of unanswerable questions. It seems that science is not equal to the task of explaining everything, especially when it comes to the intricacies of human character.

Andrew Bennett

Search

Categorías

Noticias recientes

-

Mini Camp: Easter Wonderland

3 febrero, 2026 -

MAKERS LAB STEAM CLUB: NEW ADVENTURES

3 febrero, 2026 -

Desde las aulas. Investigación y creación del profesorado en el Instituto Internacional

12 enero, 2026